There is very little history on the North West Meatworks, constructed on Babbage Island in 1920. Today the footprint of the buildings and structures are still visible, if you know where to look. And for a few people, memories remain of a childhood growing up on Babbage Island and living in some of the remnant buildings in the 1940’s.

I have researched this chapter through countless hours of reading newspaper articles in the marvelous online archive of Trove. This research provided me the best clue yet as to why the building on Lot 147 North River Road was affectionately called the Elephant House by the Sanderson family.

The first part of this chapter is my interpretation of a newspaper report of a meeting of pastoralists on 7 July 1918 with the Edward Angelo MLA, Minister for the Gascoyne. The meeting was held on Boolathana Station. Having visited Boolthana Station many times, I have taken some licence with the narrative, however the facts and figures are reproduced as per the newspaper report.

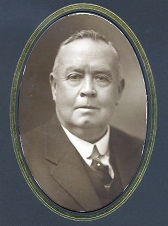

Edward Angelo MLA Member for the Gascoyne 1917 – 1933

Selling a Dream

7 July 1918

Edward Angelo marvelled at the grand homestead as he travelled along the final stretch of the dusty road to Boolathana Station. Even more impressive was the large shearing shed they drove past as they rounded to pull up under the welcomed shade of large poinsianna tree. The progress undertaken by the Butcher brothers was mightily impressive. He was looking forward to seeing the bore rig that was drawing water to supply the dam which was pleasantly placed in close proximity to the homestead, shearing shed and other buildings.

Elected to state parliament just one year before Edward was a relatively new member of parliament. He had found his role had changed considerably from being the mayor of Carnarvon. Now he was in a much more influential position and better placed to increase government investment in the Gascoyne region. Having lived in the town since 1902, originally to open the new Union Bank on Robinson Street, he realised there were many commercial interests that would serve his own financial standing. First he was elected to the municipal council, a role that allowed him to influence the future of the town and his own fortunes. Then, in 1910 he was appointed mayor and oversaw all business for the town until 1915. Now, as a member of parliament for the Gascoyne and the North, he pursued a pet project of his.. to build a meatworks and cannery business in the town.

“Hello and welcome,” Charles Butcher called out as he walked out from under the shade of the wide expansive verandah. Edward replied heartily and shook his hand.

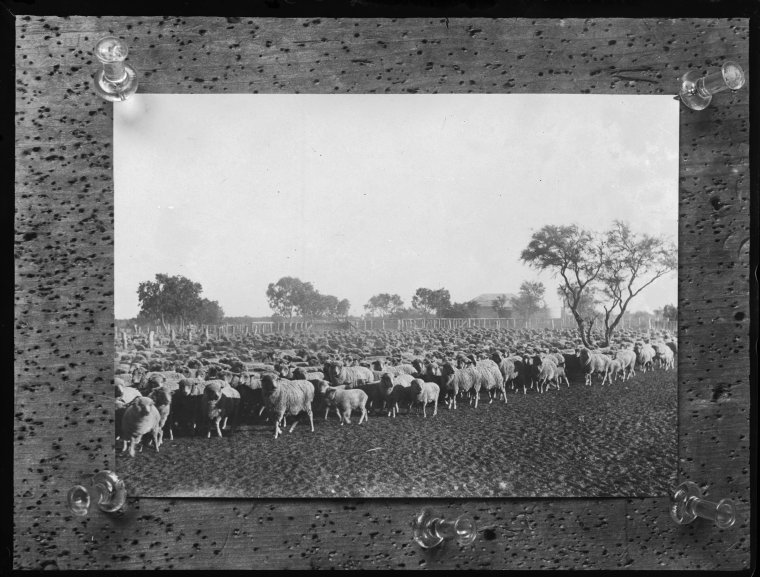

“I can see you have made further improvements to your operation here Butcher. The flock of sheep we came through down the road look fat and full of fleece,” Edward said. “I think the meeting we will have here today will be of utmost importance to the future profitability of Boolathana Station.”

Three other men joined them. Charles Atkins had travelled from Murgoo Station in the Murchison region and Frank Craig and George Gooch had travelled from stations located a little closer within the Gascoyne region. It was an important meeting to discuss the proposed North West Meatworks and these provisional directors were to talk about the issuing of shares.

“Let’s take a walk first,” Charles Butcher said and motioned for the group to follow him. It was a warm dry day for July. In the far distance thunder clouds were building on the horizon. A dry wind blew clouds of dust into the sky.

The first stop was to inspect the weir which had been built across the Boolathana Creek. The expanse of water was 300 yards wide at the widest point and 14 feet deep. Charles explained that they intended to utilise a portion of the water for irrigation purposes.

The men then walked towards the large shearing shed where Charles explained how it was constructed, at a cost of £4000. The massive arched roof and timber slatted decking, sheep runs and the pens could handle several hundred sheep at one time. The heady smell of lanolin and sheep manure rose up through the timber slated floor.

They left the shearing shed and walked a little further to inspect a new artesian bore. The fifth to be installed on Boolathana to a depth of 2.500 feet. It cost the pastoralist £5000. A necessary expense to sustain the expanding flock of sheep Boolathana was preparing to stock. All this investment provided the station the capability of carrying an additional 8,000 to 10,000 sheep. Charles explained to the men that a sixth bore was scheduled in the coming months.

Charles Butcher had made extensive improvements to the profitability of the station. With 40,000 head of sheep and expansion planned, this was a tremendous example for Edward Angelo to demonstrate, back in the chambers of Parliament, the need for a processing plant in Carnarvon.

“With regard to your meatworks proposal Edward, you have my word that we will be founding shareholders. I intend to carry an additional fifty percent of stock when the meatworks is functional and will alter my grazing policy to support it.” Charles Butcher exclaimed.

“Currently we breed on Boolathana and fatten at my brother’s southern Meeberrie Station before taking the sheep overland to the south. If this meatworks gets off the ground, and is built in Carnarvon, we will change the way we handle the sheep and breed at Meeberrie and then fatten at Boolathana, to be closer to the processing plant.”

Edward was impressed with size and quality of the sheep and lambs he had seen. A vigorous hand shake sealed the arrangement and confirmed a supply of 20,000 lambs to the meat works during a normal season.

The Project is a Winner …On Paper

The initial proposal for the meatworks and canning factory started to take shape in the early 1910’s. The sheep industry had grown significantly across the north west and there were moves to establish processing facilities in a number of locations across the northern part of the state as far north as Wyndham.

In 1916 a group of prominent Carnarvon businessmen, mostly pastoralists, started to canvass the need to slaughter and process sheep from within the Gascoyne district, closer to where the stock was bred. Their names are synonymous with Carnarvon’s history: Frank Craig, George Gooch, Keith Harper, Jas Nicholas, Dennis Matheson, Edward Angelo, Frank Whitlock and Reginald Burt. This group of local business men developed the original proposal and subsequently became the founding directors of the North West Meatworks Ltd. They secured land on Babbage Island and set about developing the initial business plan. Then they sought additional shareholders and a commitment from pastorialists from across the Gascoyne and Murchison region to meet the stock number required to make the processing factory viable.

To support the proposal and provide confidence to the shareholders, a refrigerant expert from Queensland was engaged to prepare a report. The report identified that in order for the facility to be profitable the facility it would need to process 1500 sheep a day. This capacity would support a canning process that would supply the growing demand for tinned food, in this case mutton, which had become popular during the first world war. The report referred to a tremendous stock holding of sheep across the Gascoyne that could supply the facility and a global demand for canned meat driven by the disruption that World War I had on live sheep exports. Such a facility required an investment of £50,000.

By 1917, the business group had secured £45,000 and a government loan of £30,000. The first meeting of shareholders of the Nor-West Meat Works, Ltd. was held in Perth at the Weld Chambers in October 1918. Chaired by Mr Angelo, M.L.A. it was reported that sufficient capital had been raised to permit of the company being floated, a site had been secured, and the Colonial Treasurer had agreed to grant the company a loan or £30.000. This loan added to the capital raised, would give the company £75,000, which was considered sufficient to build the required infrastructure and also to allow for a working fund.

The proponents confidently announced the meat works would be in operation by the end of the 1919. The plans were well developed and ready for an immediate start. Filled with confidence the business men touted the project across national and international news papers, proudly espousing a high quality canned food; produced using the latest technology and state of the art refrigeration. Besides meat, they intended to expand the line to include canned fish providing a processing option for the Shark Bay fishermen. With excitement and optimism of employment for returned soldiers the project was considered a state government priority at the end of the Great War.

Plagued with Problems

In 1919 a project manager with engineering experience was engaged, the land on Babbage Island cleared and the foundations laid. However, it did not progress as planned. Issues prevailed with the supply and transporting of materials and the project was hampered with the inability to secure the necessary engineering skills to install the equipment. The project was plagued with problem after problem. Significant delays resulted in substantial cost overruns.

What was also missing from the proposal was an assessment of the risk associated with prolonged drought and the post war global depression. Both these events wrought havoc on the project. Sheep numbers were decimated during a long period of drought and the returns for wool sales plummeted.

Four years later when the project finally reached completion in 1923, the town was impacted by a flood. The facility, built near the mouth of the Gascoyne River, was not spared the effects of the flood. This flooding event further exasperated the pastoral industry which had been in the grip of a three year drought and stock holdings were more than halved. It would take years to rebuild the stock numbers required to support the factory.

By July 1924 the venture was reported as a complete failure. Not one animal, neither sheep nor fish, had passed through the facility and the state government had taken back control. All of the funds, including public money had been lost and the local government commenced legal proceeding for payments of the rates. The buildings were boarded up and the facility mothballed.

Will a Co-Operative Save the Day?

In July 1924 attendees of a meeting in Perth at the Weld Club were advised that a group of shareholders held in Carnarvon had passed a resolution to have the shareholder entity changed from a company to a co-operative arrangement. A representative for the local pastoralists was a Mr Jackman from Calligiddy Station, who read the report of the Carnarvon meeting and spoke at some length in support of the motion. The chairman pointed out that the original prospectus resulted in the company being registered under the Companies Act. The directors would not be able to consider this new approach until all parties had the opportunity of saying whether they agreed to the alteration or not.

John Forrest proposed a committee, consisting of Jackman, and Le Vaux, be appointed to help the company’s solicitor in preparing the articles of association. This new approach required a further 20,000 shares to be raised and several of those present at the meeting promised to approach the larger pastoralists and urge them to subscribe the balance. Several speakers stressed the necessity of immediately launching the company so that operations, could begin for the next season. However, the efforts were in vain. The additional funds were not raised and a co-operative arrangement was not agreed to.

The facility failed to commence operations in 1925.

The White Elephant of the North West

Another five years past and once again, in 1930, government advisors inspected the facility. Again, the benefits of the facility, if it could be made functional, was promoted as a great asset for the town. And for a second time, a report was prepared. This report highlighted the great benefits for the town and district. Even if just one aspect the facility operated for part of the year it would be an outlet for culled ewes and other sheep. This report went further, highlighting the benefit to public health by reducing the breeding of flies from animals left to die and rot in the paddock. It also identified that jobs created would extend to drovers, lumpers and tanners and more ships would call at the One Mile Jetty.

However, the government of the day blamed the failure of the meat works squarely on drought and the lack of livestock . The final death knell for the facility came in 1934 when despite all efforts to fix and make operational the freezing plant it simply would not function properly. There had been an ongoing issue with the operations of the plant and equipment which could not be resolved.

Some 15 years since construction had commenced, the North West Meatworks, unable to commence operations and suffering significant financial losses was considered to be a complete failure. Newspaper reports called the project the ‘White Elephant of North West.’ This became the catch phrase for the failed enterprise and heralded warnings for other grand projects. Efforts to recoup some of the losses commenced through demolishing and selling off whatever could be salvaged. Machinery that could be salvaged, at least that which was operational, was shipped to the abattoirs in Wyndham.

In 1934 a tender was put out for the sale of all salvageable material. The Australian Inland Mission (AIM) purchased the meat works dining room and moved it into the centre of town and re-assembled it as a recreation room for a Single Mens’ Lodging House. The lodging house was built in Egan Street, and provided a much-needed facility to accommodate the many men travelling through the northern regions in search of work. The AIM reported it would cost between £400 and £500 to re-purpose the building with dividing walls creating space for a billiards room, library and games rooms. It is a reasonable assumption that Stan Sanderson stayed in the lodging house when he first arrived in Carnarvon in search of work.

It was around this time, that bricks and timber frames were purchased by Dr Fergusson-Stewart to construct a building to accommodate a housekeeper and provide a storage loft. The salvaged materials were transported to the plantation and re-constructed about fifty metres from the main house near the packing shed in direct line to the pump shed located on the river bank.

What is in a name? Everything it seems. With newspapers from the West Australian, The Daily News and the Northern Times adopting the phase ‘The Elephant of the North West’ for the failed project. It became synonymous with the project that proved to be worthless, useless and unable to be readily disposed. The building on the Sanderson plantation, born from the North West Meatworks, carried a version of this name forward. I would not described the repurposed building as worthless or useless. In fact it was quite the opposite.

In the next chapter I will reveal the family member who possessed the wit and humour to embellish the building on the Sanderson plantation with the name of The Elephant House.

Footnote: The images included in this page have been sourced from the State Library of WA